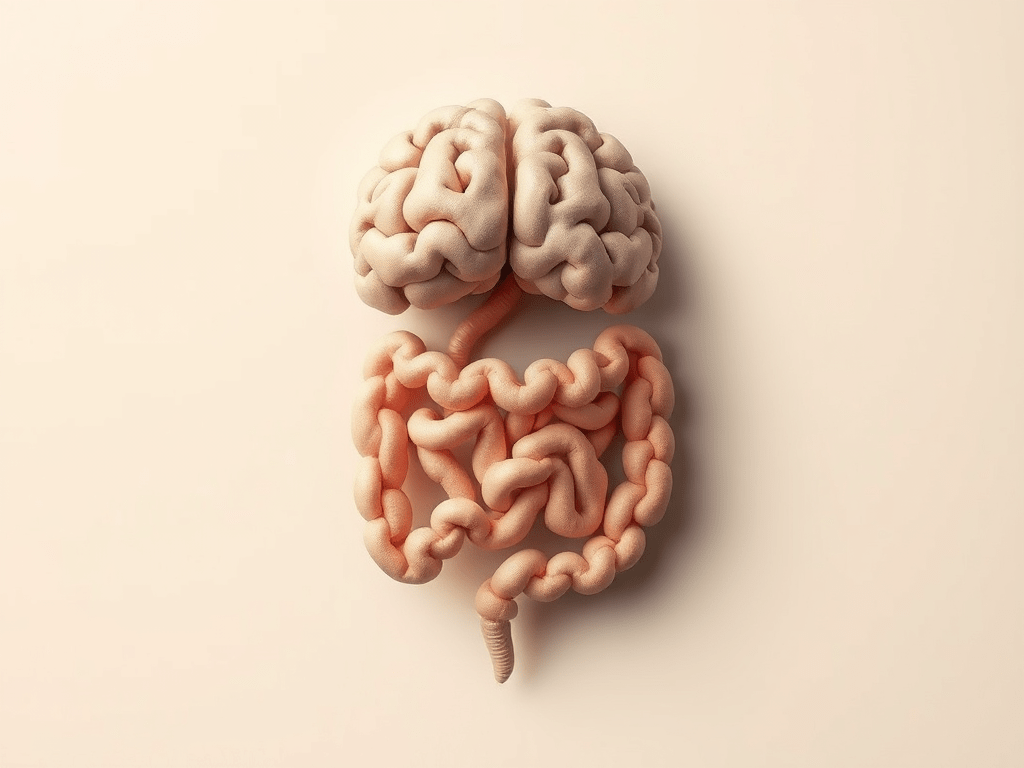

I’m sure we’ve all wondered why some people completely light up and become the life of the party in a crowd, whilst others prefer quiet, one to one conversations. Recent neuroscientific research reveals that these stark personality differences aren’t just behavioural preferences, but differences in both brain structure and function. Let’s explore the contrasting worlds of introversion, extroversion, and some of the other personality types that lie somewhere in between.

The Classic Divide: Introverts vs. Extroverts

When Carl Jung first coined the term introvert and extrovert in 1921 (Thorne, 2010), there was no idea that it would become deeply embedded in how we understand and choose to explain someones’ entire personality. It was said that introverts typically prefer quiet environments, process information deeply before responding, and often feel energised by solitary activities. Whilst on the other hand, extroverts lean towards being outgoing, tend to think out loud, and gain energy from social interactions. At the time these seemed like simple behavioural observations, however, they’ve now been validated by brain imaging technology, revealing real neurological differences between these personality types.

The Physical Differences in Brain Structure

Research published in the Journal of Neuroscience found that introverts had larger, thicker gray matter in their prefrontal cortex (DeYoung et al., 2010). This is the area of the brain associated with abstract thought and decision-making. Extroverts had thinner gray matter in that same area. This structural difference may explain why introverts tend to engage in more reflective thinking and careful analysis before making decisions.

Conversely, some neuroimaging studies have shown that extroverts have greater grey matter volume in the bilateral dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) compared to introverts (Lai et al., 2019). These regions of the brain are involved in cognitive control and goal-directed behaviour, and may reflect the differences in regulation abilities between both personality types.

The Neurotransmitter Connection: Dopamine vs. Acetylcholine

One of the most fascinating aspects of personality neuroscience involves how different brains respond to neurotransmitters. These are the chemical messengers that influence our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

Extroverts have more dopamine receptors in their brains than introverts do (Hansen, 2016)! This finding means that extroverts need to be in more stimulating environments so more dopamine is released and they feel happier, because they are less sensitive to it. Dopamine is associated with reward-seeking behavior, social interaction, and the motivation to pursue external stimulation. This explains why extroverts often seek out social situations, novel experiences, and external rewards. Their brains literally require more stimulation to achieve the same level of satisfaction.

Introverts, on the other hand, appear to be more sensitive to acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter associated with introspection, and the ability to feel content in calm environments. Acetylcholine is released when in calm and mentally engaging activities, and this explains why introverts often feel overwhelmed in highly stimulating environments and prefer more quiet activities that allow for deeper processing.

Brain Activity Patterns

Advanced brain imaging has shown that even at rest different personality types show different activity patterns. Studies have also found that in a relaxed state, the introverted brain was more active, with increased blood flow (Johnson et al., 1999). This research suggests that introverts’ brains are naturally more active internally, and this may explain why they appear quieter as more of their energy is already being used for internal processing.

The Middle Ground: Ambiverts and the Balanced Brain

While the introvert-extrovert split captures significant neurological differences, research suggests that most people exhibit a mix of introverted and extroverted traits rather than extremes of either. This has led to recognition of ambiverts as one of the most common personality types. These are individuals who fall somewhere in the middle of the personality spectrum. They feel comfortable in social situations but also enjoy time alone, balancing between outgoing and reserved behaviours.

From a neuroscience perspective, ambiverts most likely have brain structures and neurotransmitter sensitivities that fall between the extremes seen in introverts and extroverts. This balanced neurological profile allows them to be comfortable in both social and solitary situations.

Understanding Omniverts

A newer concept in personality psychology is the omnivert. This is someone who experiences dramatic swings between introverted and extroverted behavior. Where ambiverts can balance both the traits of introversion and extroversion, an omnivert fluctuates between both depending on the situation or mood. One day they could be the life of the party, and the next they might want to be completely by themselves. Not much of an inbetween.

Whilst research on omniverts is still limited, their extreme behavioural shifts might reflect highly sensitive neural systems that respond dramatically to environmental cues and chemical fluctuations.

Otroverts and Authentic Self-Expression

Recently, Rami Kaminski introduced a much newer concept in personality psychology: the ‘otrovert’. This is someone who doesn’t feel a sense of belonging to any group, and often just energise themselves. An otrovert is a person that is more defined by their originality and independence, not by how much they love or avoid people. Otroverts have the ability to move fluidly between social and individual spaces, guided by authenticity.

However, as of yet the term otrovert is much newer and not yet formally recognised in psychology. This means its’ neurological basis remains largely unexplored. However, the concept suggests that some individuals may have brain patterns that prioritise authenticity and independence over what defines other personality types.

The Help of Brain Plasticity

Whilst many studies have shown that these different personality types have clear neurological foundations, brain plasticity means that these patterns aren’t completely fixed. Chronic stress, significant life events, and other factors can lead to shifts in both brain structure and personality expression (Xu & Potenza, 2012). This does not mean an introvert will magically become an extrovert, but they can, with time, develop better skills for navigating extroverted situations when necessary.

The Importance of Neurological Diversity

The research is clear. Personality differences aren’t just cultural constructs or personal choices, they reflect genuine differences in how our brains are structured and function. Some brains just function differently than others, and this diversity is one of our greatest strengths.

Whether you’re an introvert who needs quiet time to recharge, an extrovert who thrives on social energy, an ambivert who is flexible and adapts to different situations, or an omnivert who experiences dramatic shifts in personality, your brain’s unique patterns are extremely valuable!

References:

- DeYoung, C.G., Hirsh, J.B., Shane, M.S., Papademetris, X., Rajeevan, N. and Gray, J.R. (2010). Testing Predictions From Personality Neuroscience: Brain Structure and the Big Five. Psychological Science, [online] 21(6), pp.820–828. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610370159.

- Hansen, M. (2016). Introverts and Extroverts: The Brain Chemistry Behind Their Differences – Therapy Changes. [online] Therapy Changes. Available at: https://therapychanges.com/blog/2016/12/introverts-extroverts-brain-chemistry-differences/.

- Johnson, D.L., Wiebe, J.S., Gold, S.M., Andreasen, N.C., Hichwa, R.D., Watkins, G.L. and Boles Ponto, L.L. (1999). Cerebral blood flow and personality: a positron emission tomography study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, [online] 156(2), pp.252–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.2.252.

- Lai, H., Wang, S., Zhao, Y., Zhang, L., Yang, C. and Gong, Q. (2019). Brain gray matter correlates of extraversion: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of voxel‐based morphometry studies. Human Brain Mapping, 40(14), pp.4038–4057. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24684.

- Potenza, M.N. (2013). Neurobiology of gambling behaviors. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23(4), pp.660–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2013.03.004.

- Thorne, B.M. (2010). Introversion‐Extraversion. Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, pp.1–1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0468.

Leave a comment