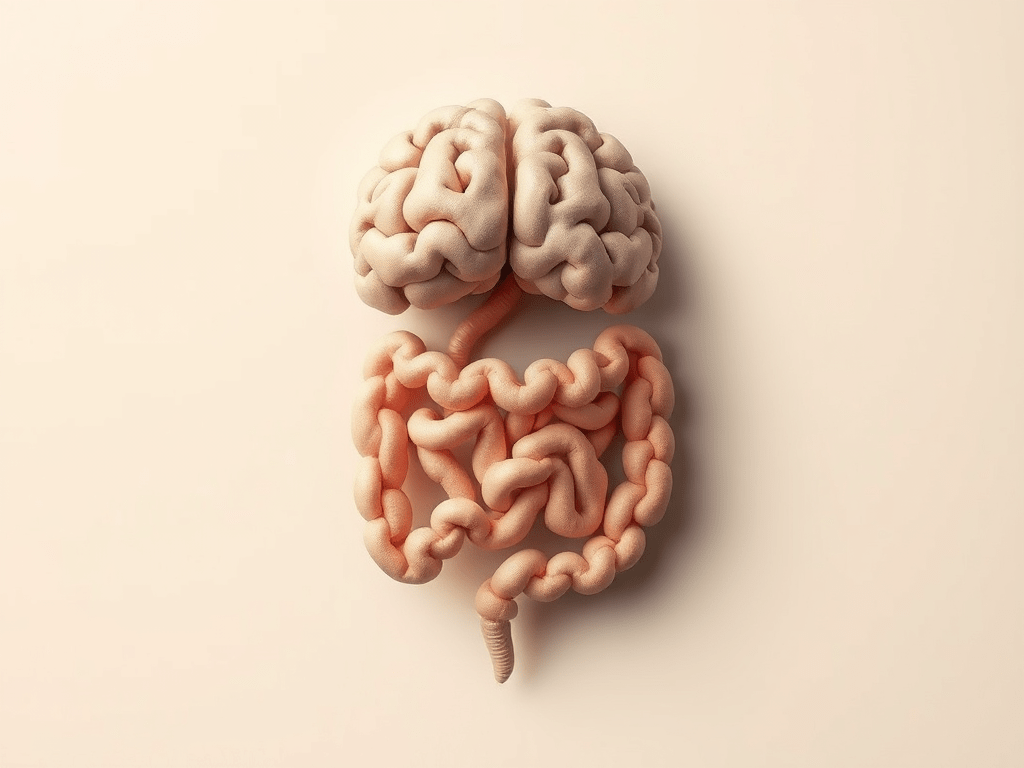

You’ve probably heard someone say they have a “gut feeling” about something, but what if that phrase is more literal than we ever imagined? Deep in your abdomen lies what scientists are now calling your “second brain”. It is a complex network of neurons that not only controls digestion, but may hold the key to understanding mental health disorders such as depression.

The Gut-Brain Axis

The GBA isn’t just a trendy wellness concept, it’s a sophisticated biological superhighway. This bidirectional communication system connects your gastrointestinal tract with your central nervous system through multiple pathways involving neurotransmitters, immune factors, and an intricate network of signalling molecules (Clapp et al., 2017).

Think of your gut as a bustling city populated by trillions of bacterial residents, AKA your microbiome. These microscopic inhabitants are active participants in your mental health, producing neurotransmitters and neuroactive compounds that directly influence brain activity and mood regulation (Sharon et al., 2016). The scale of this microbial influence is staggering, with there being more bacterial cells than human cells in your entire body (Ferranti et al., 2014).

The Serotonin Surprise: Why Your Happiness Lives in Your Gut

Here’s a fact that may change how you think about depression: 95% of your body’s serotonin, the “feel-good” neurotransmitter most associated with happiness and well-being, is produced in your intestines (Terry & Margolis, 2017), not in your brain!

When your gut microbiome becomes imbalanced, serotonin production can plummet. This isn’t just a local problem confined to your digestive system, because via the GBA, these changes can affect serotonin concentrations in your central nervous system and potentially trigger depressive symptoms.

However, serotonin is just one player in this complex biochemical orchestra. Your gut bacteria also influences the production of GABA, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters that regulate mood, anxiety, and cognitive function. When this delicate ecosystem falls out of balance, the effects can be profound and far-reaching.

The Stress Connection

The gut-brain axis operates through several major systems, including the enteric nervous system, autonomic nervous system, central nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Appleton, 2018). The HPA axis is particularly crucial because it controls your body’s stress response. Research has shown that patients with depression frequently display dysregulated HPA axis activity, typically characterised by elevated cortisol levels (Varghese & Brown, 2001). Your gut microbiome plays a direct role in this dysregulation, essentially hijacking your stress response system when bacterial populations become imbalanced.

Animal studies have revealed that bacterial colonisation of the gut is essential for proper development of both the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system (Carabotti et al., 2015). This means that without the right microbiome, our nervous systems simply don’t develop normally.

The Vagus Nerve: Your Body’s Information Superhighway

At the heart of gut-brain communication lies the vagus nerve, the longest cranial nerve in your body and a critical conduit for bidirectional messaging between your gut and brain (Han et al., 2022). This neural pathway doesn’t just carry information, it actively regulates mood and stress responses.

When you’re under chronic stress, the vagus nerve’s anti-inflammatory and gut-protective functions become impaired (Tan et al., 2022). This creates a vicious cycle: stress damages gut health, which in turn sends distress signals to the brain, perpetuating and amplifying depressive symptoms.

The vagus nerve also explains why practices like deep breathing, meditation, and yoga can be so effective for mental health. These activities stimulate vagal tone, improving communication between your gut and brain whilst activating your body’s natural healing responses.

The Microbiome Depression Signature

Clinical research has identified specific bacterial signatures associated with depression. In groundbreaking studies comparing the fecal microbiota of patients with major depressive disorder to healthy individuals, researchers have found consistent patterns of microbial imbalance. One of the most significant findings involves Faecalibacterium bacteria. Depressed patients consistently show reduced levels of these beneficial microorganisms, and researchers have identified a negative correlation between Faecalibacterium abundance and the severity of depressive symptoms (Jiang et al., 2015). The more severe the depression, the fewer of these protective bacteria patients tend to have.

So, when your gut lacks these beneficial bacteria, it can’t produce the neurotransmitters and anti-inflammatory compounds your brain needs to maintain emotional balance.

Gut Inflammation

Your gut microbiome doesn’t just affect neurotransmitter production, it also controls immune responses and inflammatory processes throughout your body. When harmful bacteria outnumber beneficial ones, chronic inflammation can develop in the gastrointestinal tract and then spread systemically. This chronic inflammation creates a perfect storm for depression. Inflammatory molecules can cross the blood-brain barrier, directly affecting neural circuits involved in mood regulation. It’s like having a small fire burning in your body that slowly damages the very systems responsible for emotional well-being.

The inflammation-depression connection helps explain why people with inflammatory conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, and other gastrointestinal disorders have significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety.

Therapeutic Revolution: Treating Depression Through the Gut

Understanding the gut-brain axis is opening revolutionary new approaches to treating depression. Probiotics, which are beneficial bacteria that can be taken as supplements or consumed through fermented foods, are showing remarkable promise as therapeutic interventions for depressive symptoms. Dietary interventions, particularly Mediterranean-style diets that are rich in fiber, plant foods, and omega-3 fatty acids, have demonstrated significant improvements in mental health outcomes for people with depression (Parletta et al., 2017). The Mediterranean diet works by feeding beneficial bacteria while starving harmful ones, creating an environment where mood-supporting microorganisms can flourish. These approaches combined with lifestyle factors like regular exercise and adequate sun exposure, can literally reshape your gut microbiome and, by extension, your mental health.

Your Gut, Your Mood, Your Choice

The relationship between your gut and your brain represents one of the most exciting frontiers in mental health research. Every meal you eat, every antibiotic you take, every stress you experience affects the trillions of bacteria that influence your emotional well-being.

This knowledge is empowering because it suggests that we have more control over our mental health than we previously imagined. By nurturing our gut microbiome through thoughtful dietary choices, stress management, and lifestyle modifications, we can actively participate in supporting our emotional wellness.

Your gut truly is your second brain, and learning to care for it might be one of the most important things you can do for your mental health.

References:

- Appleton, J. (2018). The Gut-Brain Axis: Influence of Microbiota on Mood and Mental Health. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal, 17(4), 28–32.

- Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of Gastroenterology, 28(2), 203–209.

- Clapp, M., Aurora, N., Herrera, L., Bhatia, M., Wilen, E., & Wakefield, S. (2017). Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: the gut-brain axis. Clinics and Practice, 7(4).

- Ferranti, E.P., Dunbar, S.B., Dunlop, A.L. and Corwin, E.J. (2014). 20 Things you Didn’t Know About the Human gut Microbiome. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, [online] 29(6), pp.479–481.

- Han, Y., Wang, B., Gao, H., He, C., Hua, R., Liang, C., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Xin, S., & Xu, J. (2022). Vagus Nerve and Underlying Impact on the Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Behavior and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Journal of Inflammation Research, Volume 15, 6213–6230.

- Jiang, H., Ling, Z., Zhang, Y., Mao, H., Ma, Z., Yin, Y., Wang, W., Tang, W., Tan, Z., Shi, J., Li, L., & Ruan, B. (2015). Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 48(48), 186–194.

- Parletta, N., Zarnowiecki, D., Cho, J., Wilson, A., Bogomolova, S., Villani, A., Itsiopoulos, C., Niyonsenga, T., Blunden, S., Meyer, B., Segal, L., Baune, B. T., & O’Dea, K. (2017). A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutritional Neuroscience, 22(7), 474–487.

- Sharon, G., Sampson, T. R., Geschwind, D. H., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2016). The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell, 167(4), 915–932.

- Tan, C., Yan, Q., Ma, Y., Fang, J., & Yang, Y. (2022). Recognizing the role of the vagus nerve in depression from microbiota-gut brain axis. Frontiers in Neurology, 13.

- Terry, N., & Margolis, K. G. (2017). Serotonergic Mechanisms Regulating the GI Tract: Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Relevance. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 239, 319–342.

- Varghese, F. P., & Brown, E. S. (2001). The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Major Depressive Disorder: A Brief Primer for Primary Care Physicians. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 3(4), 151–155.

Leave a comment